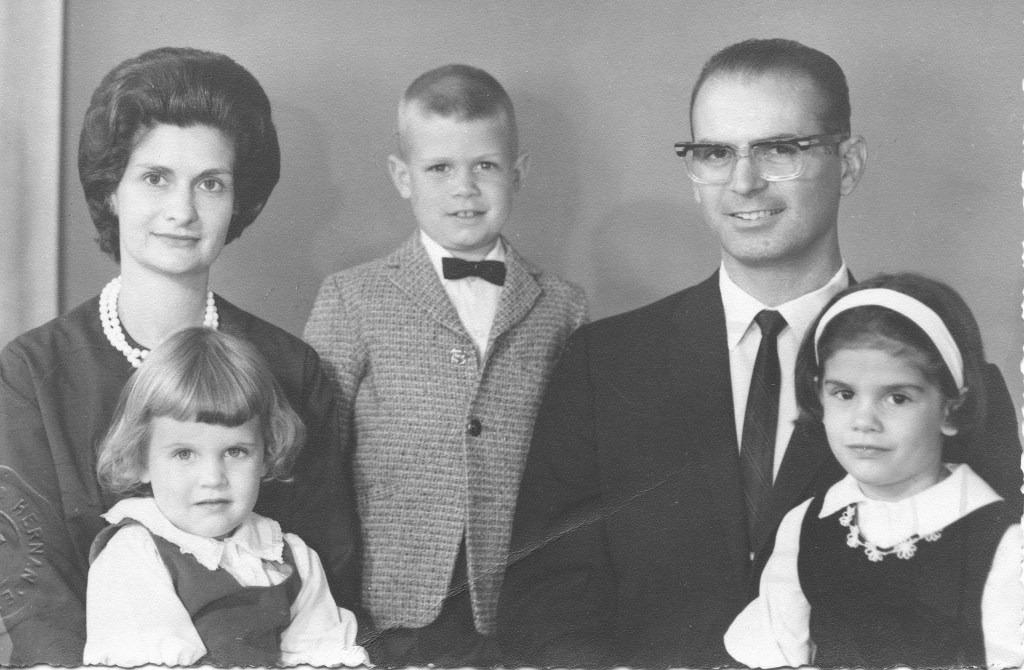

When his younger brother Marion became pastor of Sunset Road Baptist Church in Charlotte, Dad took all of us to hear him preach. As he began to speak to the congregation, he motioned toward us and welcomed us as visitors.

“My brother Bobby was like Andrew in the Bible, for he introduced me to Christ,” he said, before proceeding with his sermon. After 60 years or so, I confess I don’t remember much else he said.

I remember Dad smiled faintly and nodded his head in acknowledgement, but the moment passed quickly and I don’t remember either of them saying much about it later.

For those of you who were not raised in a church that taught its children to quote large segments of the Bible, you may not remember that Andrew, Simon’s brother, said to Simon, “This is the Messiah.” Andrew faded into the background after that, while Simon became the disciple Peter, the rock upon whom Jesus said he would build his church.

It turns out that Dad and Uncle Marion’s story was a little more dramatic than that — or that we were ever told until just a year or so ago.

According to Mom, Dad accepted Christ when he was 12 years old. He was so excited by his religious experience that he wanted to share it. He went to his little brother Marion and insisted that he, too, accept Christ. When Marion hesitated, Dad wrestled him to the ground and held him down until he agreed that he accepted Christ.

Now the Bob Lineberger that I knew as my father was a man of peace, almost always calm. He would show anger sometimes, but not very often. Like other parents of his day, he practiced spanking, but it was more Andy of Mayberry type spanking than the type people look back on as cruel and abusive.

But apparently the child Bobby was different. Shortly after he died, my old high school principal, Neb Hollis, told me that when they were classmates, he admired my Dad’s ability to fight. Although smaller than most of his schoolmates, he was not one to pick on.

“I never saw him start a fight,” Mr. Hollis told me, “but I saw him end quite a few.”

On another occasion, Mr. Hollis, a large athletic man who played triple-A baseball and also coached football, told Mom that when he was training in hand-to-hand combat as an Army paratrooper, he wished he could fight like Bobby Lineberger.

Later, Dad supported Marion as he studied for the ministry at Gardner-Webb College. Although Marion worked to earn money, he did not make enough to pay his way.

Dad didn’t have much money himself. He had sent home most of his pay while he was in the Army, with the understanding that Grandpa Charlie would put aside a small amount from each pay period as a nest-egg Dad could use to get started after his enlistment was up. The lion’s share, of course, went to Charlie to help support the family.

But when Dad came home, he learned that he had no nest-egg. Charlie wanted to be named a deacon at Mount Zion Baptist Church, and in an effort to curry favor, he got into a giving contest with some of the other church members. He gave all of Dad’s savings to the church. He was not chosen to be a deacon, but the money was gone. Dad was a faithful Christian and obedient son, so he kept silent.

He always gave a tithe (ten percent) of his earnings to the church. He started giving his tithe to Marion to help cover his college expenses. They kept this arrangement secret from Charlie, because they knew he would demand the money be given to “the family.”

Mount Zion being a small church, word soon circulated that Dad was not paying his tithe. He let most people believe that he was delinquent rather than let the secret out.

Years later, after I was grown, Dad said something that I would remember, but he gave me no hint of what he meant, and only after Mom told me this story did I understand.

“Not every Christian can preach,” he said, “but we can support those who do.”

* * *

I can’t really remember much about Uncle Marion as a preacher. I only heard him a few times. To me, he was Uncle Marion, a serious but funny and kind man whose visits were always special. After he became a missionary to Argentina, they also became rare.

He and Dad remained close even though they saw each other only once every few years. I remember Dad, who did not typically write letters, writing several pages on special airmail stationery and receiving similar letters in the mail. Airmail to foreign countries had to be written on very thin paper — translucent, almost tissue paper. The envelopes were made of the same paper and had red and blue edges, with the words, “Air Mail, Par Avion” printed on them.

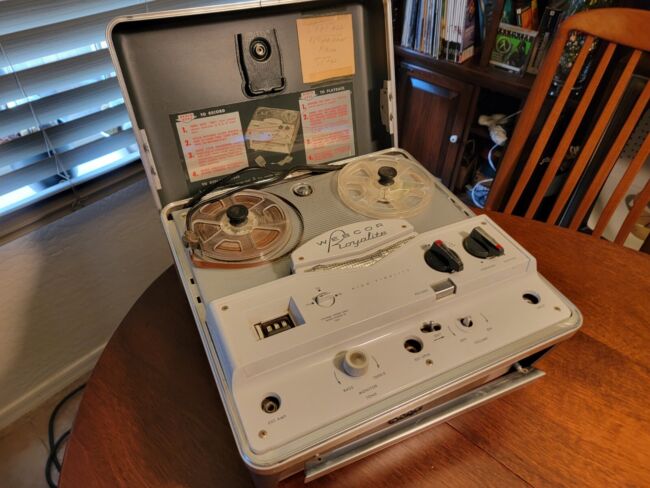

Dad also bought a reel-to-reel tape recorder (so did Aunt Margaret, as I recall) so they could send 30-minute audio tapes full of family news. When either Dad or Margaret received a tape from Marion, we gathered around the Webcor to hear the news from Argentina. Dad or Margaret would then tape a response to be mailed to Uncle Marion. We knew Dad truly loved his brother, because he hated talking on electronic devices. He did use us kids to fill up a little space on the reel when he got tired of talking.

For a while Uncle Marion had a ham radio set, and he occasionally reached amateur ham operators in the States who would call Dad so they could talk to each other through a phone patch, with the domestic long distance charges charged to our phone. (“Will you accept the charges?”a telephone operator would say before putting through the call from the ham operator.) Dad would have to say “Over” when he finished a sentence or paragraph and was ready for a response. International phone calls were prohibitively expensive, so this arrangement got the costs down enough they could afford a call every now and then.

Argentina became a politically dangerous place, and even relatively safe foreign visitors like missionaries came under suspicion. The repressive government was known to “disappear” people suspected of disloyalty, and radio and recording devices attracted suspicion. Uncle Marion got rid of his equipment, and they went back to airmail letters.

- * *

When Marion was in the States, either on furlough or after he retired from missionary work, he always had a story or two to share at family gatherings. I can remember a few of them.

At a summer camp Marion knew, the director was particularly concerned with food waste. Before a meal, the director addressed the boys in the dining room, saying,

“I expect every boy here to eat every bean and pea in his plate.”

Back when I was a child, insects were more common than they are today. Windshields always caught many of them in season, and they usually landed with a splat. When we were driving with Uncle Marion and a big bug splattered the windshield, he said, “Boy, that took guts!” (We still use that one whenever the situation arises.)

Another favorite story happened when Uncle Marion was visiting a rural church. After service, he was invited to share Sunday dinner with a large family. He accepted, of course, and soon sat down to a table loaded with great country cooking. Several times during the meal, the family members would encourage him to have more food — “Have some chicken, Preacher,” and “Please have a biscuit,” and so forth. He gratefully took more food, but eventually his plate was overloaded, so he politely said, “No, thank you,” and kept eating.

It was only later that a church member told him that in that community it was considered rude to ask anyone to pass a dish. If you wanted something, you would encourage the person sitting near the dish to have some of it. They were expected to pass the dish to you. So most of the family went through Sunday dinner without chicken or biscuits. He was mortified, of course, but he had no inkling of their custom. How rude they must have thought him, he said!

Leave a comment