When I was growing up in the 1950s and ’60s, money was usually tight. Although we didn’t use “hustle” to describe our extra jobs, almost everyone I knew did something or other to raise a little extra cash. Hustle, for those of you who don’t know the old lingo, was something your coach would encourage you to exhibit in a game or practice. In fact, MLB player Pete Rose would be nicknamed “Charlie Hustle” for his aggressive play, but before he was banished for gambling.

Dad tried to make extra money by fixing televisions and radios. When the mill he worked in started limiting hours and even doing some shutdowns and layoffs (having people “sign up,” they called it when a whole department or shift would have to go to the Employment Security Office to apply for unemployment insurance)—and when Dad started to think there might be better ways to earn a living, he bought a TV and Radio repair course. I remember the mail order school was the Massey Institute of Technology. We used to kid him about being a graduate of MIT.

Dad made a little money from his part-time business, but not a lot. He had to buy test equipment, and to get a new part for an old radio or television he would have to drive ten miles one way to the nearest parts store. When he added up his costs, he often found the total was more than he could comfortably charge. After all, his customers were family and co-workers at the mill, and he knew how tight money was for them.

As color television and transistor radios started becoming more common and printed circuits began to replace vacuum tubes, he found his training and equipment didn’t prepare him to work on the new stuff. Rather than investing more into updating his shop and skills, he gradually phased out his repair business.

When Mom and Dad got married, they both worked in the Stanley mill. Mom kept injuring her back, and she said they were spending more on doctor’s bills than she made. She decided, with Dad’s support, to give up mill work. They started their family about that time, so in many ways it was easier for her to stay home.

She sewed to save money on clothes, sewing much of what we wore. As people learned she was skilled at sewing, she was able to make a bit of money sewing for other people. A bit later, Aunt Jane Shelton (Ray’s wife) became a frequent customer. Mom says she made enough money to buy every new suit Dad bought during his life. That probably sounds a little more impressive than it actually was, because like many men in our community, Dad bought very few suits.

Mom also did a little special order baking. Grandpa Nelson loved her pound cake, and he would buy the ingredients and pay her a little extra to bake him one. As he did with all cakes, he would slice off about a quarter of the cake and, after eating it, would say, “Well the sample was good. Can I have a full serving now?”

When Mom and Dad built their house (the one Mom still lives in), it was difficult to get mortgage loans. The house was built as a “shell home,” in which the construction crew (in this case one of whom was Grandpa Charlie Lineberger) left the interior unfinished. The buyer would do the finish work, like painting and floor finishing.

Dad hired Mom’s three youngest brothers, Ray, William, and Leroy, to help with the painting. I was three years old at the time, so Leroy would have been thirteen and the other two not much older. Even though money was tight and Mom remembers it as a financial strain, Dad paid each of them a dollar a day for their work.

When I got old enough, I started doing odd jobs to make a little spending money. Dad occasionally experimented with giving us a small allowance, but for the most part we had to earn whatever money we got. The amounts were small, and I remember saving up for months to buy things I wanted. My first camera, a cheaper plastic knock-off of a cheap plastic Kodak, cost only about ten dollars, and it took me months to buy.

One early item on our wishlist was a genuine, cotton duck pup tent. It was described in the Western Auto catalog (Sears was too far away so we relied on the Stanley Western Auto and Five & Ten Cent Stores for most of our stuff) as a two-man tent, but we figured we could get all three of us in there, since we were far from man-size.

It cost a little over 20 dollars, and it would take forever to get enough money by saving our tiny allowances and meager earnings from odd jobs that Dad would pay us to do. So I asked Grandpa Nelson if he had any paying jobs I could do. Grandpa Nelson had a number of side hustles. His farm was his preferred way to make a living, but he never made enough to get by on, so it remained a side hustle.

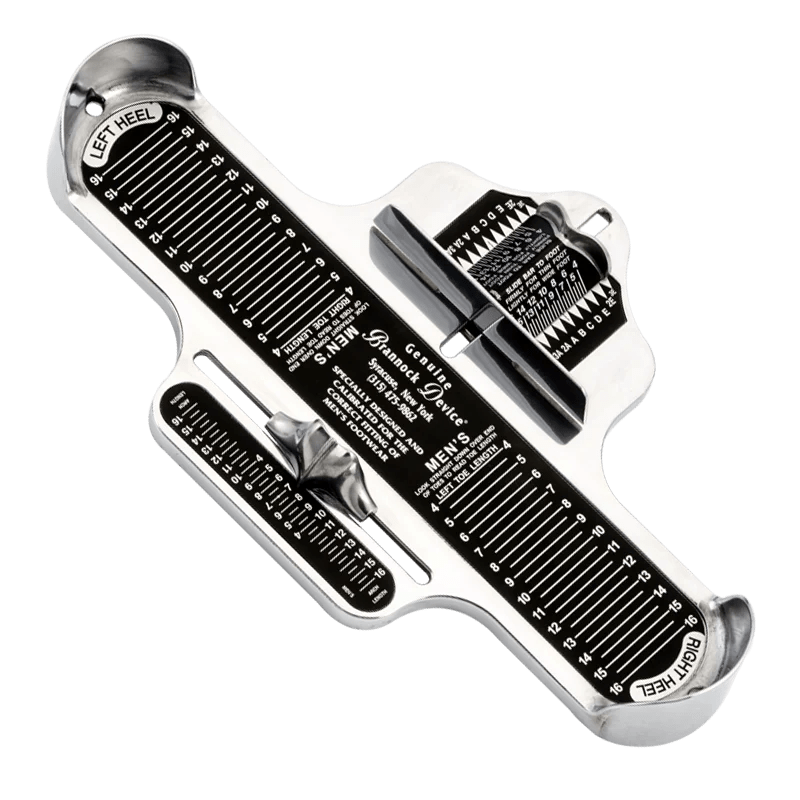

Grandpa Nelson also sold Mason shoes from a catalog. He had a genuine Brannock device, just like the ones in the shoe stores. He apparently sold Mason shoes for some time, because people would come to his house specifically to leaf through his catalog and place an order.

I remember Dad used to buy his work shoes from Nelson, and I once had a pair of deerskin shoes from the catalog. I never knew whether Dad preferred the shoes over what he could get in local stores, or if he was just trying to help out his father-in-law. After reading this, Mom said Grandpa’s shoes were the only ones that Dad found comfortable. He had bunions and other foot problems, and the Mason shoes were designed to accommodate such problems.

Nelson also loved going to the local auctions. The closest was in Alexis, in the old building next to Carl Stepp’s store. I think it was held every Friday night, or maybe every other week. Anyway, Nelson would almost always find something there that either he wanted or he thought he could sell for a profit. He was a good salesman, so he often did convince his neighbors and family to buy something he had bought cheap.

I didn’t participate in the shoe or auction business, but Grandpa hired me to pick pole beans on his truck farm. I don’t remember exactly how I was paid, but I do remember being amazed at getting a dollar or two for picking beans, something I had to do as an unpaid chore in our home garden.

One summer, Chuck and I were both paid to put up the support strings for Grandpa’s pole beans. He put up the posts and strung two wires along the row, one just above the ground, the other four or five feet high. He taught Chuck and me how to tie up the twine between the wires so that the pole beans could wrap their tendrils around the string, holding the beans off the ground.

On the early crop that already had beans ready to pick, Chuck and I picked beans and filled bushel baskets shaped sort of like conga drums. Grandpa Nelson preferred that style over the wider, shorter kind because they would fit between the narrow rows without crushing the crops. I believe we were paid 50 cents per bushel. As the other beans grew and started producing, we picked those too.

By late summer, I felt like a Rockefeller. (Note to my younger readers: the modern equivalent would be an Elon Musk or Jeff Bezos!). Pooling my money with my brother Gary’s, we had enough to buy our tent. Gary always managed to have money saved up. My little brother Charles and I both came to think of him as a bank that could help finance our latest project, if we could convince him to loosen the purse strings. He was a tough sale. Mom said he was almost as frugal as Uncle William, who the family said was “so tight he squeaked when he walked.” That’s why Gary always had more money than we did.

Anyway, we triumphantly marched into the Western Auto and ordered our tent. We had years of fun with it, but that’s a subject for another day.

When I was a bit older, Grandpa Nelson gave me a chance to earn money in a different way. He had a day job working for a company called Jenkins Reneedling. They served the textile mills that formed the basis of the area’s economy. Cotton, wool, and some synthetics went through carding machines to straighten and clean the fibers and prepare them for further processing. Some of the carding machines used sharp metal spikes, or needles, to separate the fibers. In at least some of these machines, the needles were soldered into a bed or drum, and over time they had to be replaced.

Jenkins Reneedling specialized in repairing those machines. Their process involved using solder to attach new needles where needed. I never saw how they did it, but obviously they used a lot of solder, and scraps of it fell to the floor during the work. Someone swept up the solder, along with anything else that might be on the floor, and collected the “sweeps” into shallow boxes.

The solder could be retrieved and reused by heating, thereby melting the solder and separating out the paper and other refuse. The melted, clean solder was then poured into molds, creating bars of solder that could be used just like new solder in the reneedling process.

Grandpa Nelson melted solder and resold it to Jenkins. He had let Chuck help him during his summer visits, and by the time we reached our early teen years, Chuck knew the process well enough that Grandpa let him melt solder unsupervised.

In fact, Grandpa let Chuck do almost anything unsupervised. Even though we are almost exactly the same age, and I was a very responsible child, I was never trusted to do the “dangerous” things on the Shelton farm. I think this was because Chuck’s father, Harold, was in his parents’ mind a born risk-taker. Grandpa and Grandma assumed Chuck could handle anything more or less safely and could figure it out if things went wrong.

I, on the other hand, was “Mi-Mi’s” child. My mother had been an insecure, shy child. She was a “scaredy cat,” so the family never expected her to take any risks. Grandma and Grandpa assumed I was like my mother, so they never let me drive the tractor or do anything else around the farm the Mi-Mi wouldn’t have done. Or maybe Grandma Estie just didn’t want to have to face Mom if I got hurt.

While I admit to being a belt-and-suspenders kind of guy, I am fully prepared to take on anything risky after I’ve analyzed it. As my daughter, Laura, says, “how many things have you fallen off of?” (Again, a subject for another post!)

The result of our enforced roles was that Chuck would drive the tractor while I sat on the flimsy fender as we experimented with how quick it could turn if you got up speed and locked up one of the main wheels and cranked the steering wheel quickly. That was far more dangerous than letting me drive, of course, but our grandparents never saw, or asked, what we were doing.

Anyway, once we were old enough, Grandpa let Chuck and me melt solder. It was after Nelson and Estie had moved into the trailer, but before Chuck and I had our driver’s licenses. The old house was now technically the property of the Sproles, but Grandpa still used it to store some of his stuff. If I remember correctly, he had not yet torn down the Old Kitchen.

The solder-melting process was actually very simple. Chuck and I used one of the cast iron wash pots that Grandma Estie had boiled the laundry in. We dumped in a box or two of sweeps from Jenkins Reneedling that Grandpa Nelson unloaded for us before he left for work. Then we piled wood under the pot and lit a fire, just as Estie had done on laundry day.

As the fire heated the pot, the solder would gradually melt, forming a beautiful silver liquid topped by a random mixture of paper, dirt, and other trash. We would use sticks lit in the fire to set the burnables like paper on fire, then wait for those to burn off. Then we would skim off the dirt and other trash that didn’t burn. Eventually we would have a caldron of liquid solder, as pure and clean as when it was first created.

Then we would use a cast iron ladle to fill the molds Nelson had provided, and wait for the solder to cool and harden. That resulted in large blocks of solder. I don’t remember how much they weighed, but they were about a foot long and about one-and-a-half inches wide and thick. If we filled each mold correctly, the weight would be within a range that Jenkins would accept and pay Grandpa for. I think we weighed them, but I’m sure Nelson did after he came home from work. Any that didn’t pass muster were laid aside and remelted and molded in the next round.

The good bars were stacked in his car and delivered the next day to Jenkins. I don’t remember how much Grandpa Nelson made on each bar, or how much he paid us—maybe 50 cents or a dollar per bar. I’m sure it wasn’t much by today’s standards, but we felt pretty rich after a good round of solder melting.

Leave a comment