Assorted memories

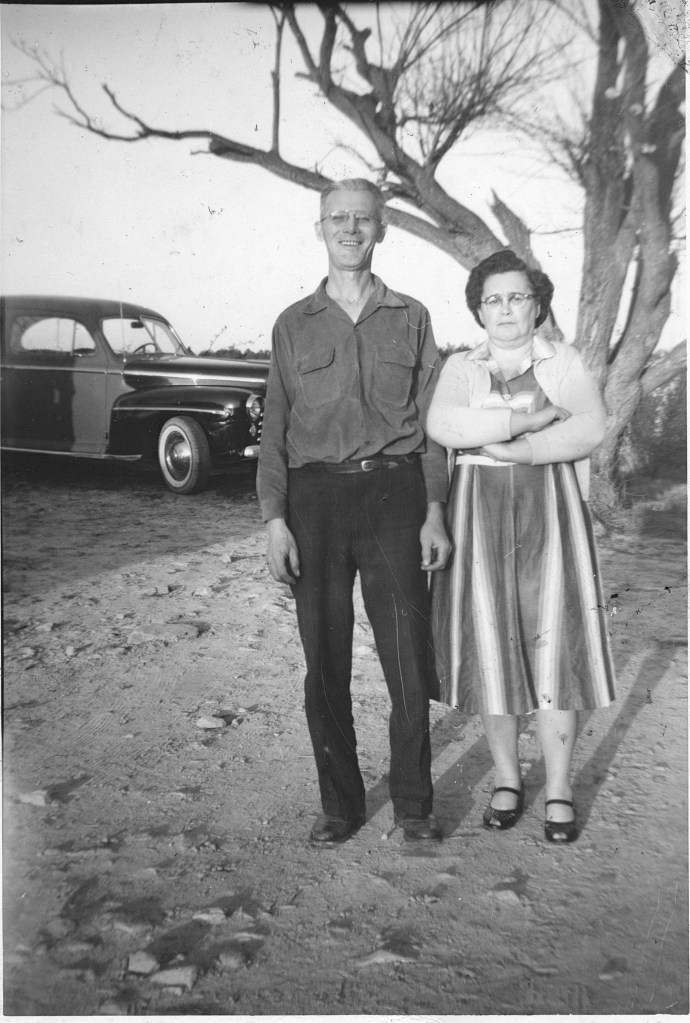

A quick Internet search suggests this starting memory happened in 1962. Chuck Shelton was staying with Grandpa and Grandma Shelton for what we came to call his yearly sabbatical, although at age 10 or 11 I doubt we knew that word yet.

Chuck and I are first cousins, both born in July 1951. Beyond that we had very little in common, although we got along very well as children, and I usually spent at lot of time at our grandparents’ house when he came to stay a week or so every summer. We found our different personalities and interests led to a greater opportunity for finding fun things to do. We also had long-running debates. We never did agree, for instance, whether NASCAR or Indy-car racing was better.

Anyway, some evening during the early summer of 1962, Chuck and I were sitting on the settee in the fire room of the Shelton house, watching the old black and white television with Grandma and Grandpa. The summer rerun of the premier episode of Beverly Hillbillies came on, featuring the scene when Granny Daisy Mae Moses declares to Jed Clampett that she is not leaving their cabin to move to California with the rest of the family. She sits stubbornly in her rocking chair. The next scene is the one that appeared in the show’s opening, when Granny and her rocker are perched atop the old truck.

Grandma Estie laughed louder and longer than I ever saw her, before or after. That stubborn old Granny, she declared, was the funniest thing she had ever seen.

Chuck and I carefully exchanged giggles. Our Granny (although you couldn’t call her that) was every bit as stubborn and feisty and lovable as the one on TV.

In fact, I became convinced that Irene Ryan (the actor who played Granny) must have known Estie Shelton at some point. The personalities were certainly alike, although our Grandma didn’t do the acrobatics Granny sometimes did. And there were some physical similarities. Granny’s facial expressions even looked a bit like Estie’s.

Although Irene was much thinner than Estie, they were of similar height. I remember Grandma used to say she was “a little under five feet,” when anyone asked.

“Standing on a box, maybe,” Uncle Leroy once muttered under his breath. Mom has variously remembered 4’11” to 4’9″. I remember 4’9″.

If you ever watched the Beverly Hillbillies, you probably saw Granny standing at the foot of the fancy stairs yelling for Jethro to get up and come downstairs. I’ve mentioned in previous posts that Grandma did not go back upstairs after she came down in the morning, so I clearly remember her standing at the foot of the stairs yelling “Leroy! Get out of that bed!”

Granny Moses used to call herself an M.D. (Mountain Doctor) and she had a remedy for everything. Mom says Estie never called herself a doctor, but she had a remedy for anything that might ail anyone. Most cures involved poltices applied to the patient’s chest, most often a mustard plaster.

Mom says that Estie never used olive oil for cooking, but she did use it for earaches. A drop or two in the ear seemed to help, she remembers.

One definite difference between Daisy Mae and Estie, though. While both Grannies were famous country cooks, Grandma Estie did not cook possum. Even when Grandpa Nelson shot one and brought it home, she refused. She said they were nasty and greasy and stunk up the house. So Nelson’s possums were cooked by his his Aunt Maggie and eaten elsewhere.

In fact, Estie was famous for her cooking. She cooked simple foods, such as the vegetables they grew on the farm, along with chicken or ham or occasionally beef they also raised. As far as I know, she never cooked a casserole. But if you ate at her house, you would be served the best green beans, corn, squash, okra, and potatoes you ever tasted. Actually, I don’t think she ever cooked potatoes—she served “spuds.” Her daughters learned to cook at her side, but while they all were good cooks, they could never match her.

Estie’s real claim to cooking fame was her biscuits, which she called hoecakes for reasons I could never find out. (Traditional hoecakes are made with cornmeal. These were all white wheat flour.) The hoecakes were shaped by hand directly from the big bowl she mixed them in, never rolled. She packed them tightly in one side of the biggest pan that would fit her oven. The resulting biscuits were thick and large, akin to what’s now called “cat-head biscuits,” although I never heard that term as a boy. In the other half of the pan, Estie patted out the biscuit dough into a single flattened loaf. We called it “biscuit bread.” Both the hoecakes and biscuit bread were brown and crisp on the outside, and light as clouds on the inside. She made them everyday, and usually made a second pan to feed the dogs. She would walk out the back door and toss the dogs’ panful into the yard, triggering a mad scramble by the 10-20 hunting dogs Nelson always kept. Mom said this ritual started because otherwise the dogs would push through the door into the kitchen if they smelled her taking biscuits out of the oven.

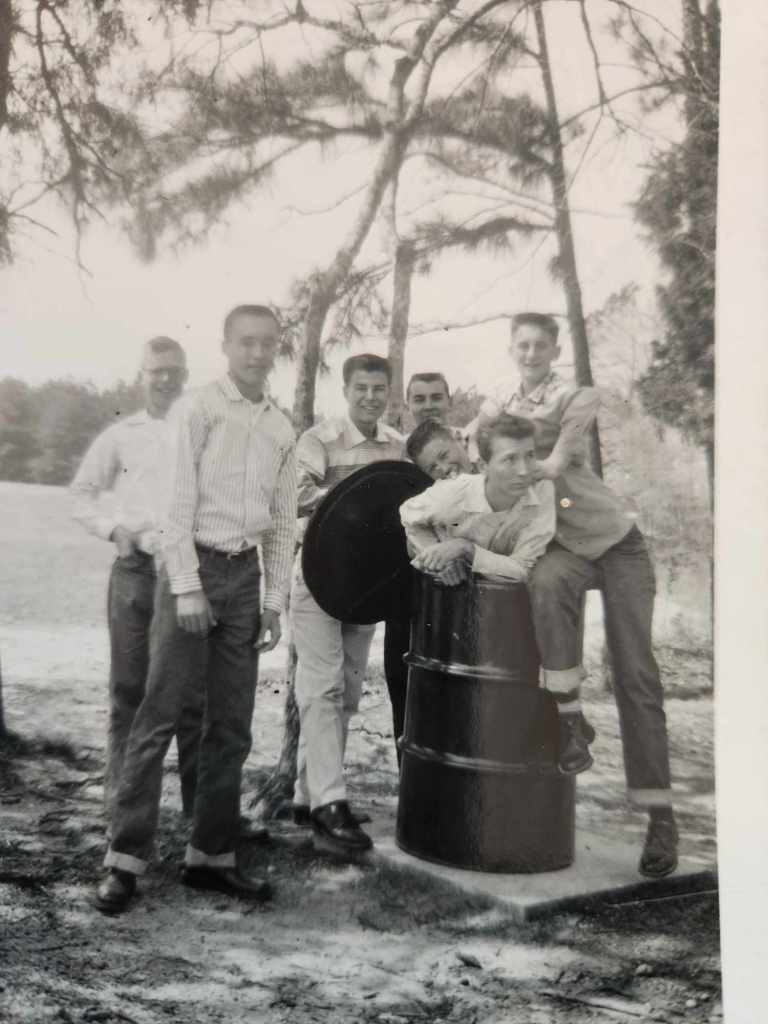

Estie loved children, and many of the people who grew up in Alexis spent time at the Shelton place. Some of the boys used to camp near the old spring with her younger boys, Leroy, William, and Ray. Estie would often show up with a pot of homemade vegetable soup and a basket of “hoecakes.”

Camping became so popular that they built a cabin in the woods near the spring. “They did a good job,” Mom remembers. “You could have lived in it.”

In case you think I’m exaggerating about the heavenly nature of Grandma Estie’s biscuits, Mom’s neighbor, James Hovis, told her years after Estie had died that he heard some of the men who were boys with Leroy, William, and Ray wishing they could have one of Estie Shelton’s hoecakes. I’ve also been told by at least one of them, Jerry Helderman, that the hoecakes were the best biscuits ever.

No one could ever replicate Estie’s recipe. Like many cooks of her era, her measurements were not reproducible. She used a large bowl for mixing each batch of biscuits, and she knew by habit how much flour, milk, and other ingredients to put in. Originally she used lard, but when she discovered Crisco she started using it. She did not roll out the dough, but mixed it by hand, then shaped each biscuit in her hands before putting it into the pan. Mom remembers that she and her sisters, Doris and Irene, watched carefully and tried to repeat the process, but it never came out quite the same as Estie’s. Doris came closest, Mom says. I remember that Mom made (and still makes) excellent biscuits, but they were a different style than Grandma’s.

- * *

Estie had a difficult childhood. Mom says her father, Peter Paul Shipman, was “shiftless” and mean. He would move the family into a rental place, then move them again before the rent came due. Thus Estie never had a stable home. Estie had to drop out of school in the second grade and go to work in the textile mill.

Therefore, while Estie was quite intelligent, she was not educated. I remember she loved to read, and she always took a book or two with her when she went with Grandpa Nelson on his fishing trips to the beach. She would sit in the car and read for hours while he fished.

Her favorite books were young adult adventure novels, which she often let us borrow when she had finished them. I remember a couple of western titles, based on popular TV shows of the day, Bat Masterson among them. She also had a book of Tall Tales, which she eventually gave to me.

Estie had her own understanding of nature, and some of her “knowledge” still pops up every now and then, so much so that I have to consult the Internet to check on some of what she taught me.

For example, she called the five-lined skink a “scorpion.” According to her, if you chopped off its tail, it would grow a new one. And the tail would grow a new lizard. Scorpions had a poisonous tail and could sting you with it, so never chop the tail off a scorpion or you would be doubling your risk of getting stung.

The Carolina Green Anole was, of course, a “chameleon.” That’s not an uncommon name for it, because it can change between green and brown.

A black racer snake could outrun you, Estie told us, but if you got too close, it could grab its tail in its mouth and roll away like a hoop. Actually, her book of tall tales described a hoop snake that could do the same thing.

* * *

Mom only recently revealed to me that Estie’s father, P.P. Shipman, was also a child molester – “dirty old man,” Mom called him. All the young girls he knew were subject to his molestations, including Estie. Even when he came to stay with the family as an old man, Mom and her sisters had to lock their bedroom door at night to keep him out. Mom said he wasn’t allowed to stay very long.

* * *

Estie was emotional and could at times be shrill. Grandpa Nelson caught most of the grief in the times I remember. But he was easy-going, almost to a fault, and she rarely got much of a rise out of him.

“Nelson!” she would yell. He would usually just grin and do what he wanted. Occasionally, if she didn’t stop yelling at him, he would grin even broader and say, “Hesh, Old Woman.”

My parents didn’t behave toward each other that way, and I couldn’t quite understand it. I came to the conclusion that Grandma Estie didn’t love Grandpa Nelson.

Then one day when I happened to be at their house, Estie got a call from someone telling her that Nelson had been in an car accident. He was not hurt, and in fact was sitting in a patrolman’s car filling out the accident report. He would be home as soon as he finished.

Estie became hysterical. Nothing anyone could do calmed her down, and even though she stopped screaming after a few minutes, she didn’t begin to recover until Grandpa Nelson arrived home and she could see that he was fine.

I didn’t quite understand what I witnessed, but I knew from then on that Estie truly loved her husband.

* * *

After reading this blog, Mom told me about a conversation between Dickie Shelton (Nelson’s nephew, son of Ben Shelton), her and some of the other siblings. None of them could remember ever seeing their parents kiss or even hug. Mom said when Nelson was sick, Estie gave him a kiss, and Mom was so shocked that she got sick to her stomach.

* * *

Grandma and Grandpa met through work, I believe. Both worked in textile mills beginning as children. Estie went to work as soon as her father could get away with sending her. Nelson got further in his education, but he did not finish school. I thought I remembered he stopped after fifth grade, although Mom said recently she thinks it was a bit further.

* * *

When people came to visit them, by tradition and habit, the men talked to Nelson and the women talked to Estie. If the visit was at night or in bad weather, Grandpa Nelson couldn’t take the menfolk outside. The conversations would start at normal volumes, but Estie would gradually raise her voice to overcome the men’s talking. Nelson would respond by talking a little louder. Soon they would both be practically yelling while sitting just a couple of feet apart. As the visitors came to realize how loud the room had gotten, they would often start laughing. Somehow Estie and Nelson never saw the humor.

* * *

By the time they ended up in Shelby, they were experienced mill hands. They were recruited when the Lilly mill started, Nelson as a weaver and Estie as a spinner. They were given a house rent-free if they would work in the start-up.

Even though people visited the Shelton farm regularly, Grandma Estie was a bit of a recluse by the time I can remember. She stopped working in the textile mills as soon as she could, and she spent most weekdays at home alone. She rarely even left the house. I remember her putting on a cloth bonnet or a large straw hat to go to the garden to gather vegetables, but only for a short time in the mornings. She did the washing out behind the house, but retreated inside as soon as it was done.

She kept flowers and potted plants on the front porch, but I don’t remember any inside. She stepped onto the porch to water her plants as needed. She kept a prickly pear cactus on a shelf at the south end of the front porch, and she had some flowers in a planter one of her brothers had carved out of a large rock. On Fridays she would ride to Stanley with Nelson to get groceries, but I don’t remember her leaving the farm much otherwise.

* * *

I have a vague memory that a visitor to the farm found hemp growing in the yard. They remarked that it was illegal to grow hemp, just like marijuana. Estie said she had inherited the plant when Nelson bought the property, and she liked the way it looked. Nobody ever said anything before. If they want me to stop growing it, they can come and get it, she said.

Mom remembers the hemp plant, and says it was already there when they moved into the house. She also remembers Estie refusing to remove it.

Leave a comment