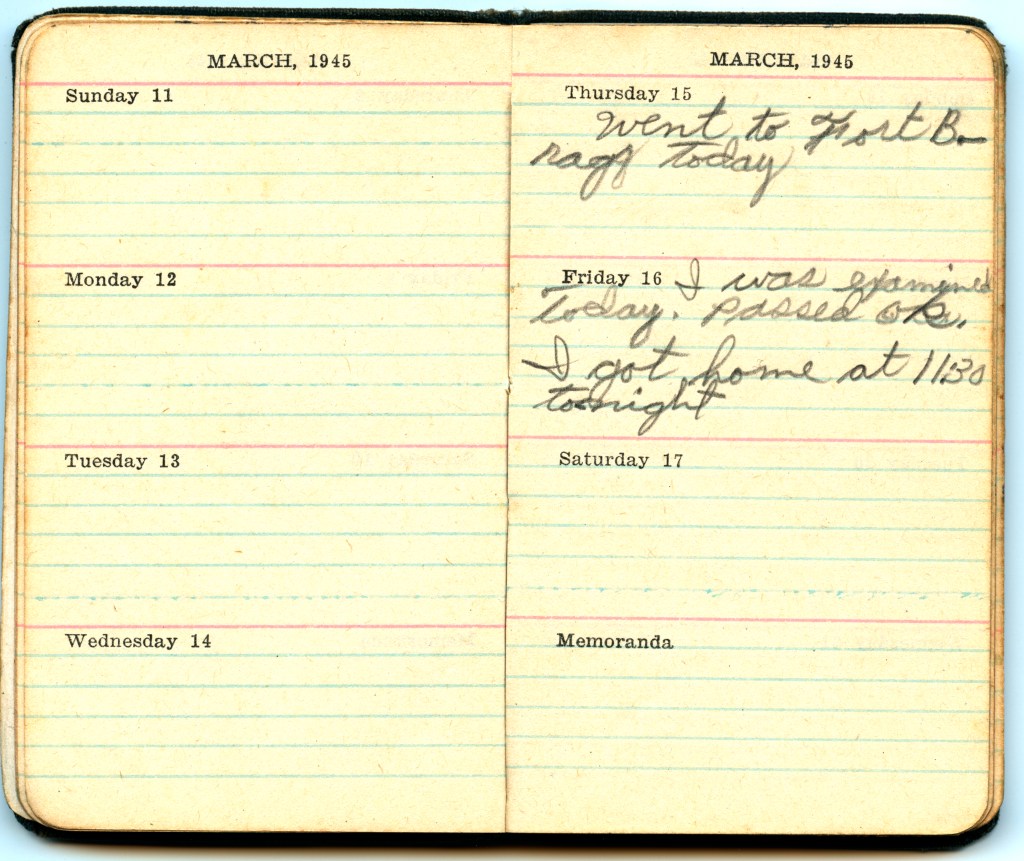

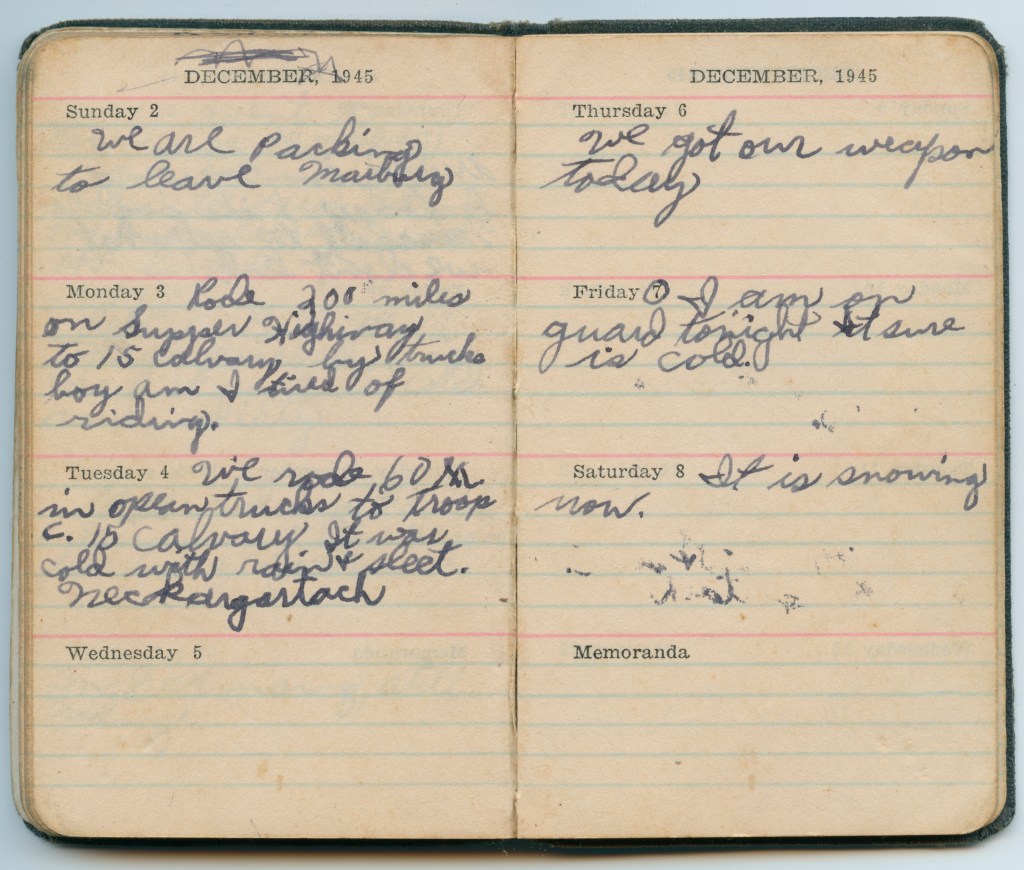

After dropping out of school to help with his family’s expenses, Dad (Robert Neal Lineberger, Sr., or “Bob” or “Bobby”) received his notice to appear at Fort Bragg, NC for his draft physical. He carried with him a small pocket calendar, which he carried throughout his Army service. He jotted a few cryptic notes about some of his experiences, but there’s not much detail.

When he returned from service, he told Grandpa Charlie that he did not want to talk about anything that happened, and he would prefer that no one in the family ask him questions. Charlie spread the word, and his wishes were honored. According to Uncle Danny, Dad did occasionally offer some stories, but they dealt mostly with food. Dad told them that he and another soldier started hunting rabbits around their camp because they got tired of Army rations and the goat meat they could obtain.

After he married and we children came along, he apparently came to terms with some of his memories, and he often told stories at the table. He never talked about actual combat, and so I assumed he had not seen any action. After seeing his pocket calendar, I’m not sure anymore.

Years after his death, I filed to get copies his military records, but I was told that his records were lost in a fire at the repository that destroyed many World War II service records. We do have his discharge form, and I’ve seen a copy of it and his draft card online.

So here is what I can remember of the stories he told us, and what I found in his diary.

Dad was originally drafted into the 82nd Airborne, ordered to report for duty on May 23, 1945. Germany surrendered on May 7, but the war still raged in the Pacific, and Germany had to be disarmed.

He said that when he got his first Army haircut, the barber asked very politely, “Would you like to keep your sideburns?” Dad said, “Oh, that would be great! Am I allowed to do that?”

“Sure thing,” replied the barber. Then with two quick swipes of the electric razor, he sliced off both sideburns and handed them to Dad. “Keep ’em anywhere you’d like.”

Basic training at Fort McClellan in Anniston, Alabama, was about nine weeks long. He described having to crawl under barbed wire while they fired live ammunition over everyone’s heads. Anyone who panicked and stood up would be automatically excused from further training and sent home in a bag appropriate for burial. He also described training in the woods and his group often having to wait until big snakes crawled across the path.

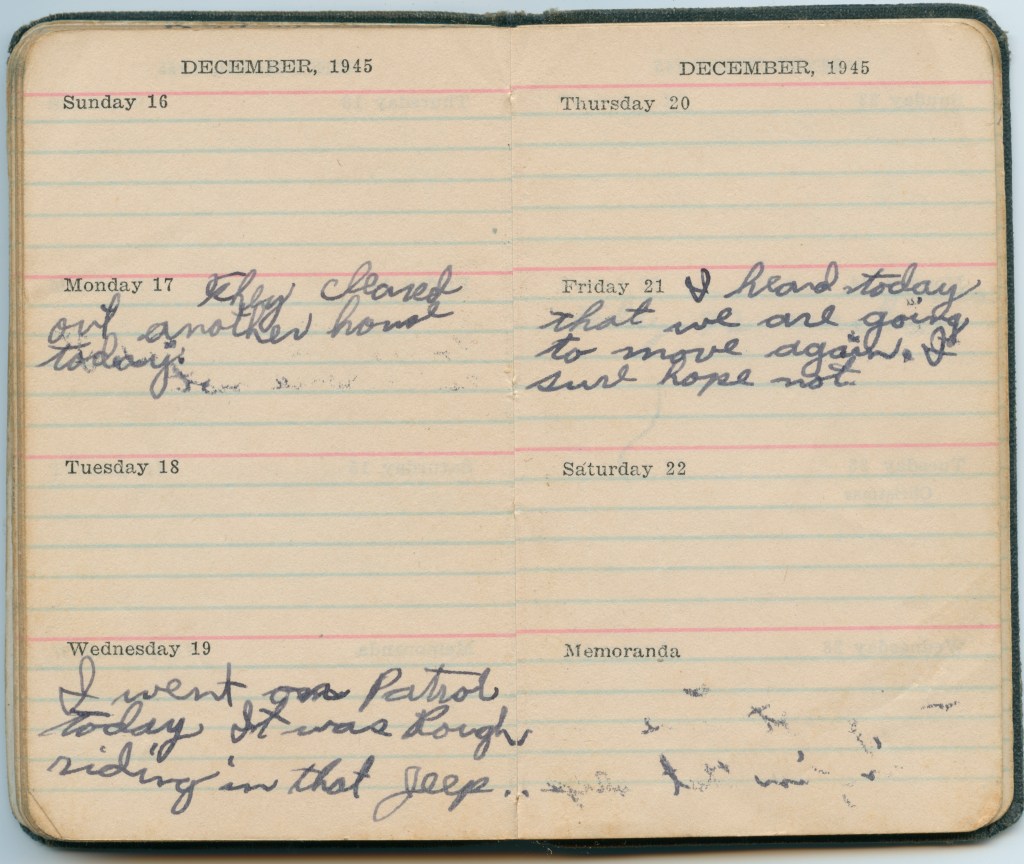

I don’t know what additional training he had after basic, but his discharge paper lists training in truck driving and the M1 rifle. He told us he drove a half-track in Europe, plus a jeep for the Colonel who was his commanding officer. His rank was originally private, of course, but in April 1946 he was promoted to Tec 5, or Technical Corporal.

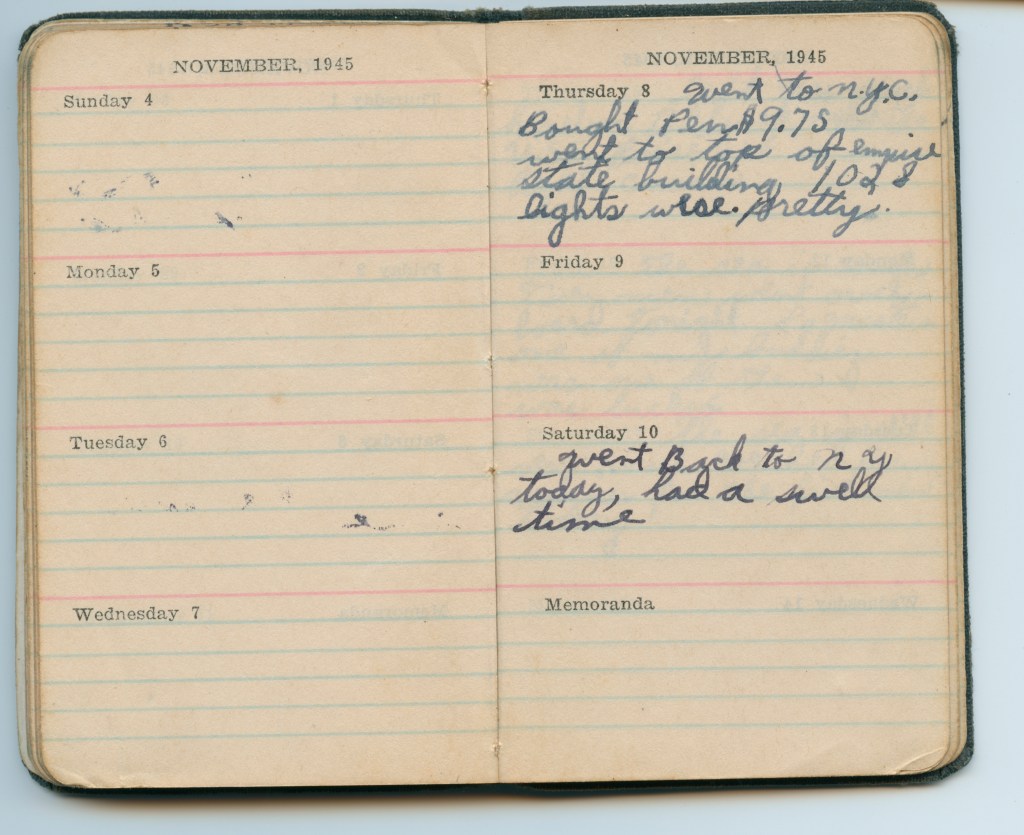

The first real note in his book about Army experience after that deals with being in New York City. He told us that he had to march in a parade of the 82nd Airborne. I found a newsreel of the final parade for the 82nd, which noted that the army was so depleted that they had to borrow troops from several other divisions to fill out the parade. Dad didn’t make a note about that in his book, and he was in Europe by the time of their Final Victory Parade in January 1946, so I’m not sure what parade he marched in. The main thing he talked about was that everyone in his troop got demerits for not polishing the bottoms of their boots before the parade (nobody told them to do it when they ordered them to spit-shine their boots), and then getting demerits for having spit-shined boots when they reached Europe and went on patrol.

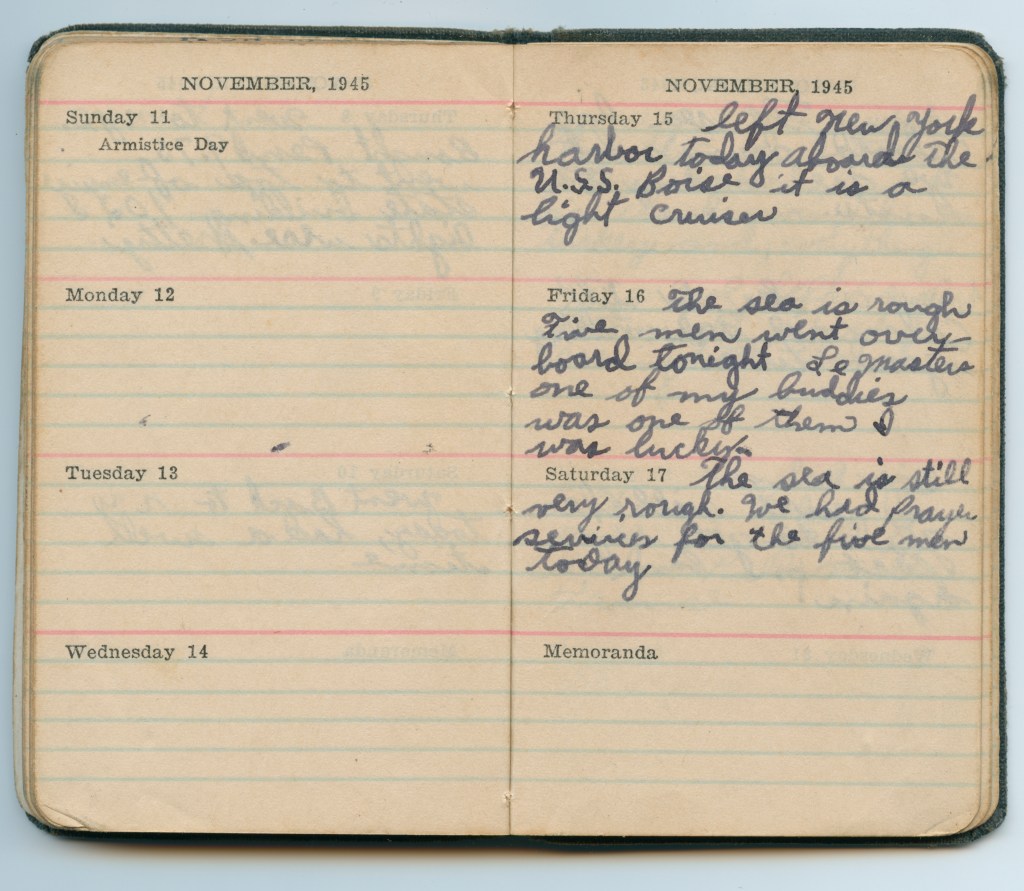

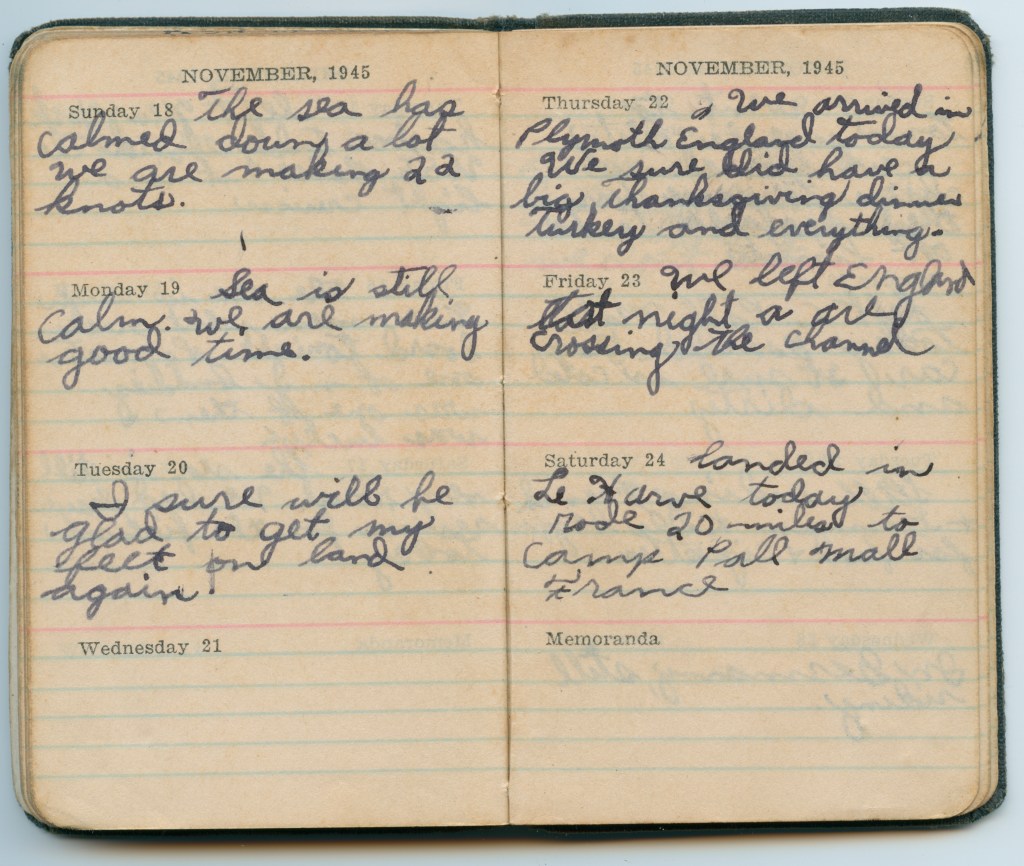

Dad was transported to England on the U.S.S. Boise on one of its last missions before being retired from active service. It had served as General MacArthur’s flagship during his duty in the Philippines, according to online sources. Dad never mentioned that, but he did talk about how rough the crossing was. “Waves higher than this house,” he would say. He told us five men were washed overboard. When I was old enough to think about it, I asked if they had stopped and tried to rescue the men. He answered that the Army didn’t do things like that, because they might endanger the whole ship if they got off course.

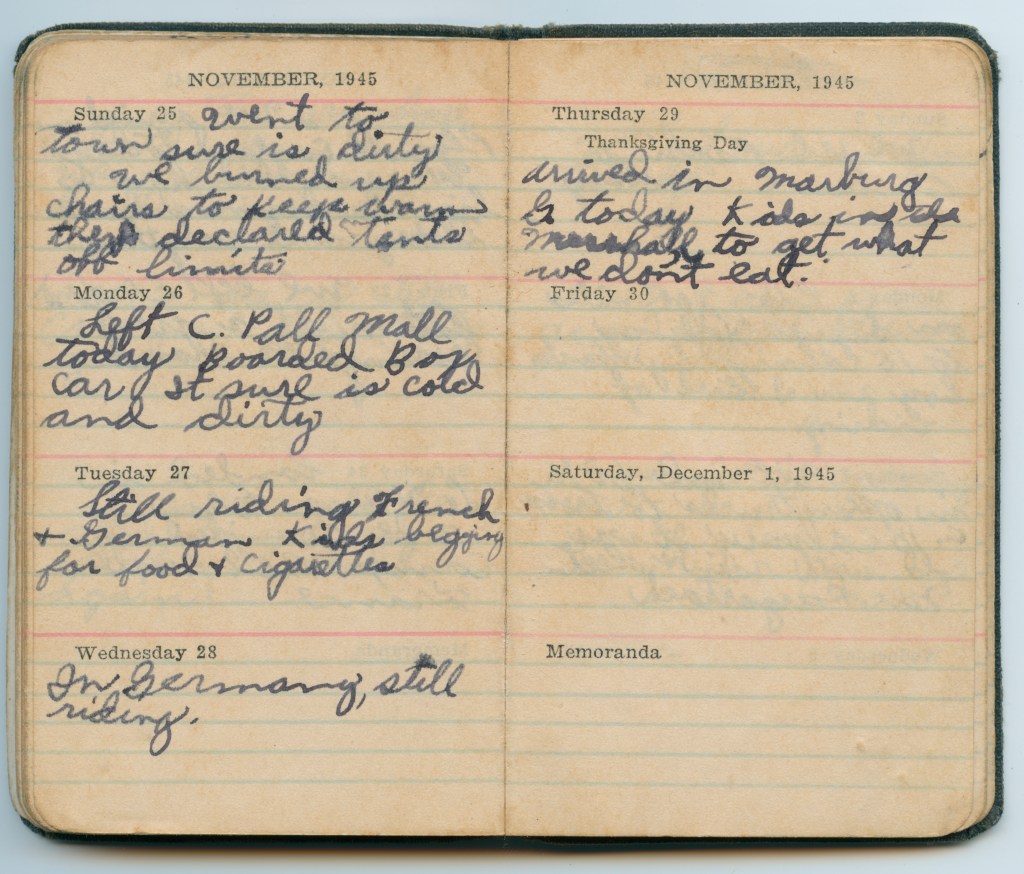

Dad didn’t talk about his experience in England, but he did make some notes in the diary. He was there for Thanksgiving 1945. He crossed the channel to Le Havre and was taken to Camp Pall Mall.

By the way, Camp Pall Mall was one of the Cigarette Camps set up in France after D-Day. They were named after popular cigarette brands and not for where they were located for security reasons.

He talked a little about traveling across France, but apparently they didn’t stop to socialize.

Dad had been transferred to the 15th Cavalry Constabulary, Troop C, according to his discharge paper. I don’t recall he ever said, but I remember he let us play with his 82nd Airborne AA patch, probably because it didn’t mean that much to him. I regret to say that it has been lost.

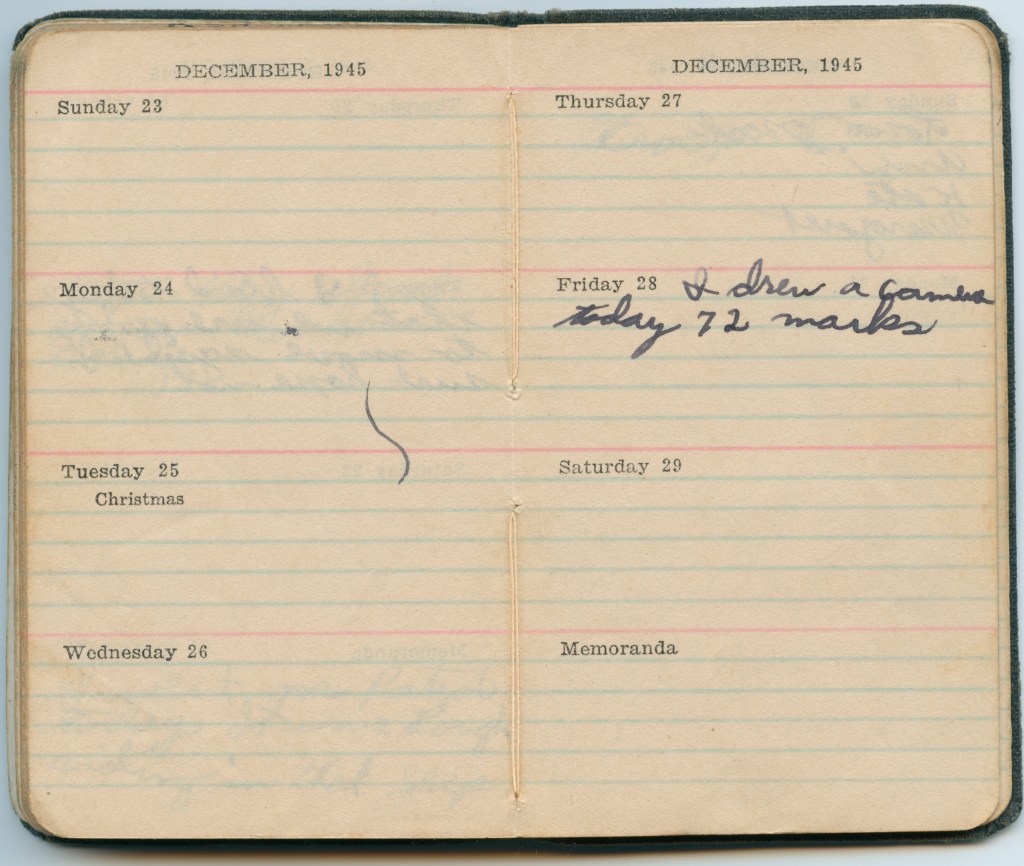

What Dad told us about his experience in the Constabulary is even sketchier than his notes in the calendar. I remember he talked about befriending local Germans. At first the army did not allow “fraternization,” but soon changed to a policy of allowing and even encouraging the GIs to get to know the locals.

Mom has some jewelry that a German girl gave Dad. She said the girl was hoping to marry a GI and go to the States.

Dad also talked about getting film developed in town and laughing about the language barrier. Learning his name, someone would ask him “are you German?” and he would say “Nein.”

“You say, nine, I say ten!” the townspeople would reply.

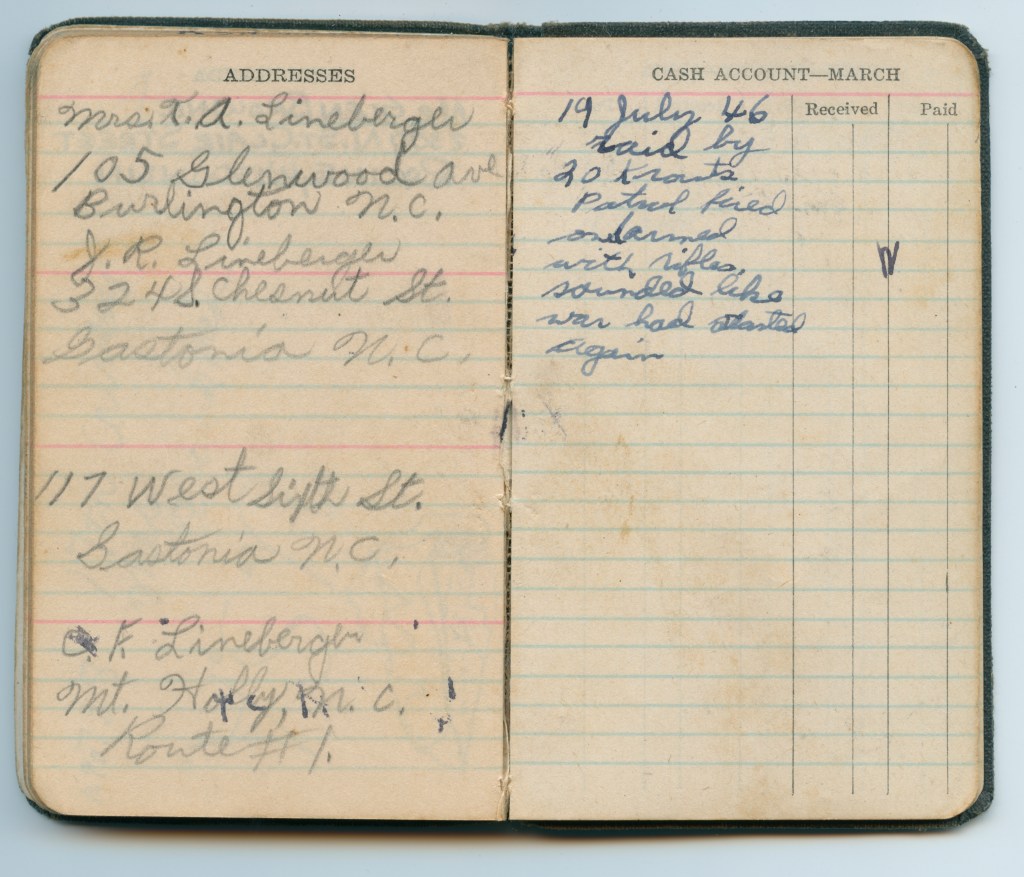

Dad never mentioned encountering any armed Germans. I remember asking him if he ever fired at anyone, but I can’t remember what he said. It seems he changed the subject and avoided answering.

He did tell us that he had his first taste of beer in Germany. He said his troop went into a meeting hall just after the Germans had left, and the food was still warm on the table. He found some beer and tasted it. He didn’t like it.

In addition to talking about hunting to supplement the Army food his troop was tired of, Dad talked about driving the jeep for his colonel. He remembered driving to the site of General Patton’s accident so the Colonel could work on the investigation. Patton died a short time later, and a service was held in Heidelberg, where the coffin was escorted by a platoon of the 15th Cavalry, Patton’s unit when he began his military service. Dad never mentioned that, so I doubt he was among the funeral platoon.

Dad talked about one time he was driving the Colonel through a town, and they came upon a crowd of people blocking the street. “Drive around them,” said the Colonel.

“But, sir, that’s the sidewalk. I can’t drive on the sidewalk,” Dad protested.

“Son, one thing you have to learn. There’s three ways to do anything-a right way, a wrong way, and the Army way. This is the Army. Now get up on that sidewalk!”

By the time of Dad’s deployment, the Army needed troops only for demilitarization and until the transition to civilian government and law enforcement could take place. It began to ship combat troops out, and the size of its forces in Europe was shrinking rapidly. As Dad’s obligatory service neared its end, he was offered several chances to enter a military career. He could have gone to Officers Candidate School, he was told, and earn a commission as an officer. He was sent to several training courses dealing with law enforcement and intelligence work, he said with the hope he would find them interesting enough to accept the offers to re-enlist.

But he wanted to go home.

He never talked about how he left the Army, the trip home, or other details. I found his discharge form online, which shows that he was separated at Fort Bragg. He was given an honorable service lapel pin, universally referred to as the “ruptured duck,” which entitled the wearer to free or discounted transportation offered to returning veterans by train and bus civilian companies.

One problem he ran into, though, was that he didn’t know where “home” was. Grandpa Charlie had moved to a new farm while Dad was away, and he had not written Dad with details about where the place was. I get the impression that Charlie did not write letters, so Dad’s communication from home came mainly from some of his aunts. All Dad knew was the new address, RFD 1, Alexis, North Carolina. When he arrived in Alexis, there was no welcoming family at the station (Alexis didn’t even have a station, although the train did stop there if signaled.) He asked around, but no one knew where Charlie Lineberger’s new place might be. Finally, Dad tracked down the mailman and was able to find his way home.

Leave a comment